Why is it important to promote the four-octave vibraphone?

From Dr. Brian Graiser:

Despite its status as a relative newcomer to Western Art Music, the standard-range (3-octave, F-F) vibraphone is now considered an essential component of any percussion section. While performers, composers, and audiences have begun to realize that the extended-range vibraphone (most commonly reaching 3.5 [C-F] or 4 [C-C] octaves) is an increasingly common modern instrument, most people are unaware that music has been written for the four-octave vibraphone for 80 years, dating back to the very first composition ever to include the vibraphone (see the essay below for more information on this fascinating historical surprise)!

Considering that a growing number of professional orchestras, university studios, and even some high school music programs now possess extended-range vibraphones, I feel it is only a matter of time until, much like the acceptance of the five-octave marimba, the four-octave vibraphone is adopted as the new standard model of vibraphone, bringing with it an expanded repertoire and further means of artistic expression. Were it not for the vibraphone's limited range, I believe that its many unique capabilities (e.g. sustain, pedaling, mallet-dampening, vibrato, and numerous extended techniques such as harmonics, bowing, and pitch-bending) would likely have placed the vibraphone, and not the marimba, at the forefront of solo keyboard percussion literature long ago. Fortunately, this constraint may one day be a thing of the past, as a small but growing number of companies are producing four-octave vibraphones, including Bergerault (France), Marcon (France), Studio 49 (Germany), VanderPlas (Netherlands), DeMorrow (USA), Yamaha (Japan), and Saito Gakki (Japan).

There will of course always be a need for the 3-octave (F-F) instrument, particularly in the trunk of the gigging vibraphonist or the cramped quarters of the orchestra pit, but I believe that the next natural step in the evolution of the vibraphone and its repertoire is the acceptance of the extended range as the new normal. To that end, I have engaged in a number of projects to promote the 4-octave vibraphone, including arranging and transcribing several works for use on the 4-octave vibraphone (such as Claude Debussy's Sunken Cathedral), commissioning other composers to write new works for the instrument (such as Christien Ledroit's serenity, shattered [2010] for 4-octave vibraphone and electronics), and composing new works myself (such as my Concerto No. 1 ["Lulu"] for Four-Octave Vibraphone [2015], the world's first concerto for the extended-range vibraphone, as the culmination of my doctoral dissertation/project). However, the fate of the extended-range vibraphone truly lies in the hands of the broader community of percussionists and composers, who I hope will take up the challenge and join me in exploring the untapped potential of the instrument.

I have created this webpage to assist those individuals who share my desire to research and/or promote the four-octave vibraphone. Here, I have compiled a number of resources (which I hope to update on a regular basis), including a visual index of existing 4-octave models, historical essays, and repertoire lists. I welcome any questions or comments via my contact page, and I wish you the best of luck in your musical pursuits. Thank you for stopping by!

Despite its status as a relative newcomer to Western Art Music, the standard-range (3-octave, F-F) vibraphone is now considered an essential component of any percussion section. While performers, composers, and audiences have begun to realize that the extended-range vibraphone (most commonly reaching 3.5 [C-F] or 4 [C-C] octaves) is an increasingly common modern instrument, most people are unaware that music has been written for the four-octave vibraphone for 80 years, dating back to the very first composition ever to include the vibraphone (see the essay below for more information on this fascinating historical surprise)!

Considering that a growing number of professional orchestras, university studios, and even some high school music programs now possess extended-range vibraphones, I feel it is only a matter of time until, much like the acceptance of the five-octave marimba, the four-octave vibraphone is adopted as the new standard model of vibraphone, bringing with it an expanded repertoire and further means of artistic expression. Were it not for the vibraphone's limited range, I believe that its many unique capabilities (e.g. sustain, pedaling, mallet-dampening, vibrato, and numerous extended techniques such as harmonics, bowing, and pitch-bending) would likely have placed the vibraphone, and not the marimba, at the forefront of solo keyboard percussion literature long ago. Fortunately, this constraint may one day be a thing of the past, as a small but growing number of companies are producing four-octave vibraphones, including Bergerault (France), Marcon (France), Studio 49 (Germany), VanderPlas (Netherlands), DeMorrow (USA), Yamaha (Japan), and Saito Gakki (Japan).

There will of course always be a need for the 3-octave (F-F) instrument, particularly in the trunk of the gigging vibraphonist or the cramped quarters of the orchestra pit, but I believe that the next natural step in the evolution of the vibraphone and its repertoire is the acceptance of the extended range as the new normal. To that end, I have engaged in a number of projects to promote the 4-octave vibraphone, including arranging and transcribing several works for use on the 4-octave vibraphone (such as Claude Debussy's Sunken Cathedral), commissioning other composers to write new works for the instrument (such as Christien Ledroit's serenity, shattered [2010] for 4-octave vibraphone and electronics), and composing new works myself (such as my Concerto No. 1 ["Lulu"] for Four-Octave Vibraphone [2015], the world's first concerto for the extended-range vibraphone, as the culmination of my doctoral dissertation/project). However, the fate of the extended-range vibraphone truly lies in the hands of the broader community of percussionists and composers, who I hope will take up the challenge and join me in exploring the untapped potential of the instrument.

I have created this webpage to assist those individuals who share my desire to research and/or promote the four-octave vibraphone. Here, I have compiled a number of resources (which I hope to update on a regular basis), including a visual index of existing 4-octave models, historical essays, and repertoire lists. I welcome any questions or comments via my contact page, and I wish you the best of luck in your musical pursuits. Thank you for stopping by!

*new* updated research on the history of the 4-octave vibraphone!

On October 1-2, 2021, I gave a conference introduction and research presentation at Dél-Alföldi Ütöhangszeres Szakmai Nap és Konferencia (DUSZK) — University of Szeged Bela Bartok Faculty of Arts (Hungary), in which I shared my most up-to-date scholarly work on the vibraphone. This is actually an UPDATE of my doctoral document, excerpts of which are still available further down on this page. I invite you to read my script, which contains some truly shocking new discoveries about the history of the vibraphone!

The Deagan Catalog page for the Innovator IV- America's first four-octave vibraphoneFour-Octave Vibraphones

|

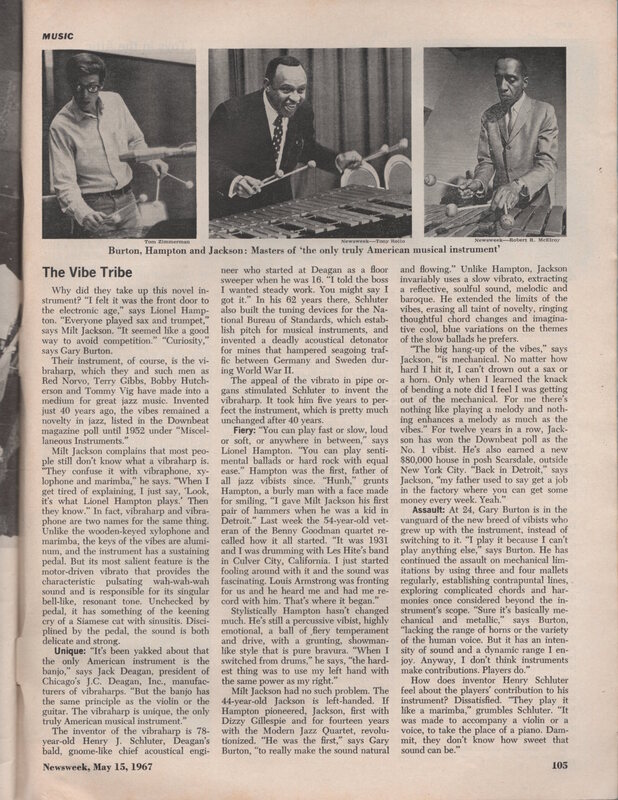

A research Gem: "The Vibe Tribe" Article

| ||||||